Share this ARTICLE with your colleagues on LinkedIn .

As a

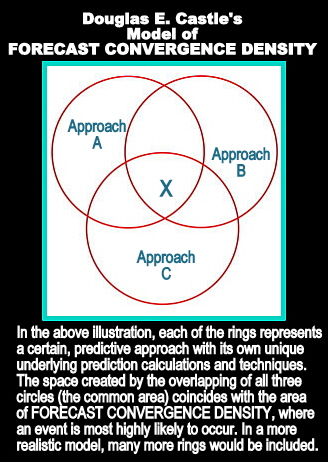

Global Futurist, I use multiple sources and multiple variables, in combination with historical trends, cycles, and other predictions made by other "Gurus" and "Pundits". I believe in three very basic ways of analyzing the future: The first is by observing historically-proven cause and effect relationships; the second is the length of certain short-term and longer-term

economic cycles; and the third is one of my favorites, which I will call "

Forecast Convergence Density".

"

Forecast Convergence Density" is a simple logical model, and dictates that "the probability of some event's occurrence is directly proportional to the percentage of a large group of diverse, different and independent predictive techniques (which I've selected) which predict that event's occurrence."

More simply put, "if the majority of the predictive approaches and the persons who champion each of them independently (to best minimize autocorrelation) and respectively say that something is going to happen, the probability that it will happen increases."

The approach is very sensible, can be easily utilized by most reasonably intelligent businesspersons, and puts its faith in a variant of the majority vote principle -- or perhaps less flatteringly, "

going with the herd."

It must be emphasized that this approach is highly simplistic and is quite inexact in terms of viability with a small number of approaches drawn, as above, as if in a part of a Venn Diagram. By my theory, reliability of the area of Forecast Convergence density increases with the number of non-auto-correlative predictive approaches used.

---------------

And, now an article culled from The Motley Fool speaks about specifically forecasting the timing (but not so much the magnitude) of various economic bubbles. In this article, we are given an idea of timing, frequency, but not amplitude of the adjustment or correction.

It's that time again.

A growing group of pessimists are asking whether the stock market is

back to bubble territory. Some are even comparing it to 1999. They say

stocks are being inflated by the Fed. That they're disconnected from the

reality of a weak economy. That they're overvalued and bound to fall.

Could they be right? Of course.

They make a forceful case with charts and ratios and historical data.

But they have been making the same argument for four years now, and

they have been wrong all the way. Clearly, the world is more complicated

than the pessimists assume.

Consider that the S and P 500 has risen as much as 60% since these quotes went to press:

"The S&P 500 is about 40 percent overvalued" -- October, 2009

"US Stocks Surge Back Toward Bubble Territory" -- January, 2010

"On a valuation basis, the S&P 500 remains about 40% above historical norms on the basis of normalized earnings." -- July, 2010

"Is The Stock Market Overvalued? Almost Every Important Measure Says Yes" -- November, 2010

"The market is as overvalued now as it was undervalued [in early

2009]," said David A. Rosenberg, chief economist and strategist for

Gluskin Sheff, an investment firm." -- March, 2010

"Andrew Smithers, an excellent economist based in London, is telling

us that we're way too optimistic, that fair value for the S&P 500 is

actually in the 700-750 range. Smithers, therefore, thinks the stock

market is about 50% overvalued." -- June, 2010

Sure, you might say these calls were just early. But let me put forth

a truism in finance: When an average business cycle lasts five years,

there is no such thing as four years ahead of the game. You are just

wrong.

Some of the bubble arguments haven't changed in the

face of a 50% rally. Take the cyclically adjusted

price/earnings ratio,

or CAPE. In 2010, the S&P 500, which traded near the 1,000 level,

had a CAPE valuation of around 22, which many pointed out was about 40%

above historic norms. Today, trading above 1,600, the S&P 500 has a

CAPE of about ... 23.

Even as the market exploded higher, the degree to

which the market is supposedly overvalued hasn't changed that much,

since companies have been busy investing in their operations and

boosting earnings. That's why being four years early means being four

years wrong.

My point here isn't to relish in other people's bad predictions --

although I never tire of doing so. And let's state loud and clear: The

higher the market goes today, the lower returns will be tomorrow. There

will be more recessions, pullbacks, crashes, and panics in the future.

But there are several lessons we can learn from four years of failed bubble predictions.

1. Never rely on single-variable analysis. Einstein said, "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler."

Wall Street blew up in 2008 after relying on mind-blowingly complex

forecasting models that attempted to measure risk out to the fifth

decimal point. Most investors now realize how flawed these complicated

models were. But then they turn around and do the opposite, dramatically

oversimplifying by trying to explain the global economy with a single

metric.

That's just as crazy.

History

tells us

that the single best gauge of

future market returns is current

valuations. But even a rational valuation measure like CAPE only has a

small amount of predictive power.

The single most powerful variable when trying to predict the future

is the "X" factor that represents human psychology, historical unknowns,

and random chance. It doesn't care about your political views or what

you think is a fair market value, and it's going to humiliate your

predictions 90% of the time.

2. Realize that some analysts are stubborn to a fault

Some

people predicted the

financial crisis in 2008. And good for them. But

many of them also predicted a financial crisis in 2007, 2006, 2005,

1997, 1995, 1992, 1985, 1970, and so on. They are perma-bears who get

ignored during booms and lionized during busts, even though their

arguments rarely change. It's the classic

broken-clock-is-right-twice-a-day syndrome.

Author Daniel Gardner wrote earlier this year:

In 2010, [Robert] Prechter said the Dow would crash to 1,000 this

year or in the near future. The media loved it. Prechter's call was

reported all over the world. Which was nice for Prechter.

Even better, very few reporters bothered to mention that Prechter has been making pretty much the same prediction since 1987.

It was similar for investor Peter Schiff. There's a

great YouTube video -- worthy of some 2.1 million views -- of Schiff predicting a market crash circa 2007. That was an excellent call. But

here's another video

of Schiff in 2002 predicting all kinds of gloom that never happened.

Sadly, that video received only a handful of views. Gardner writes in

his book

Future Babble:

[Schiff predicted the 2008 crisis,] but it's somewhat less amazing if

you bear in mind that Schiff has been making essentially the same

prediction for the same reason for many years. And the amazement fades

entirely when you learn that the man Schiff credits for his

understanding of economics -- his father, Irwin -- has been doing the

same at least since 1976.

The ideal pundit is one with a flexible mind who doesn't become

wedded to forecasts for ideological reasons. Alas, few of them exist.

3. Missing a rally can be more devastating that getting caught in a crash

The

vast majority of entrepreneurs, business leaders, policymakers,

teachers, and consumers try hard to make the world a better, more

productive place. In aggregate, they succeed the vast majority of the

time. That's why there's a strong upward bias to equity markets over

time.

It's also why missing a market rally can be a bigger risk to your

finances than getting caught up in a crash. Getting caught in a crash

usually means having to wait a few years at most -- which everyone

invested in stocks should be prepared to do. But missing a rally can be a

permanently lost opportunity. People spend so much time trying to avoid

temporary pullbacks that they forego enduring market gains. If that's

your thing, stick with bonds -- stocks aren't for you.

I can say with

high confidence that over the next 20 years we will have several severe

market pullbacks, yet stocks will trade substantially higher than they

do now.

Why focus on the former and ignore the latter?

Check back every Tuesday and Friday for Morgan Housel's columns on finance and economics.

####

Well explained and well played Mr. Morgan Housel (one of the Motley Fools). Yet I feel more comfortable predicting things using my

Forecast Convergence Density Model

.

Thank you for reading me, and for sharing my articles with your friends, colleagues and contacts through your various social media platforms and forums.

***

***

![ICS [International Connection Services] provides small to medium-sized businesses with all of the resources and tools necessary to become involved in import, export, outsourcing, global marketing, and worldwide joint venturing -- its capabilities are comprehensive, flexible, scalable and very reasonably priced. Aside from addressing virtually every significant aspect of communications, credit, financing, qualifying overseas partners (as well as distributors and representatives), logistics, customs clearance, insurance, administration and documentation, ICS specializes in custom-creating virtual international trade divisions for companies which are new to international business, and wish to absolutely minimize their expenditure and exposure in making their first advances into going global. This virtual aspect of doing business eliminates the need for additional staffing, travel, and investment in fixed costs. ICS' programs allow you to travel the entire globe and enjoy its many opportunities without ever having to leave your office! - http://www.ICSInternationalConnectionServices.com - Affiliated With Global Edge Technologies Group LLC, CrowdFunding Incubator LLC and The Internationalist Page Blog.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgfBfnNC9yTDvlooCvQiaNH4EnYQszgixmkaG_N4ayz8TbQju7lhWjcaZtaLhI6On7hcRQeH8b0YSvOsKW7bWz3vRfEmUQYJ6bI-KJwgiT7PxJnLYVXerT-7oSntQNj1p94he83RdLkcw/s320/ICS+Button+Link.jpg)

![ICS [International Connection Services] provides small to medium-sized businesses with all of the resources and tools necessary to become involved in import, export, outsourcing, global marketing, and worldwide joint venturing -- its capabilities are comprehensive, flexible, scalable and very reasonably priced. Aside from addressing virtually every significant aspect of communications, credit, financing, qualifying overseas partners (as well as distributors and representatives), logistics, customs clearance, insurance, administration and documentation, ICS specializes in custom-creating virtual international trade divisions for companies which are new to international business, and wish to absolutely minimize their expenditure and exposure in making their first advances into going global. This virtual aspect of doing business eliminates the need for additional staffing, travel, and investment in fixed costs. ICS' programs allow you to travel the entire globe and enjoy its many opportunities without ever having to leave your office! - http://www.ICSInternationalConnectionServices.com - Affiliated With Global Edge Technologies Group LLC, CrowdFunding Incubator LLC and The Internationalist Page Blog.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgfBfnNC9yTDvlooCvQiaNH4EnYQszgixmkaG_N4ayz8TbQju7lhWjcaZtaLhI6On7hcRQeH8b0YSvOsKW7bWz3vRfEmUQYJ6bI-KJwgiT7PxJnLYVXerT-7oSntQNj1p94he83RdLkcw/s320/ICS+Button+Link.jpg)